On 28 July people will head to Venezuela’s presidential election. Since the last election in 2018, the nation has suffered from one of Latin America’s worst ever humanitarian crises. Approximately 65% of residents now earn less than 100USD a month. Though lower than at the climax, annual inflation is still at 90%. This has compelled up to 7.5 million Venezuelans to emigrate. Millions more are pledging to do so depending upon the result of the election. With this backdrop, the election is one of the most pivotal in the nation’s history.

The opposition in Venezuela has now coalesced around retired diplomat Edmundo González of the Democratic Unitary Platform. This comes as the opposition’s anointed candidate, María Corina Machado, was banned from running after the Supreme Court upheld a ruling that barred her from office for 15 years for alleged tax violations and fraud. Corina Machado had previously won an illegal opposition primary that saw her win 92% of the over 2 million votes.

González was subsequently endorsed by Corina Machado and allowed to register as the lead opposition candidate. The regime also permitted several other opposition figures to run in the hope of fragmenting the opposition vote.

However, this strategy has seemingly been ineffective with the opposition unifying behind González. González has held several extremely well-attended rallies across the country on the campaign trail. However, it remains unclear whether González will be able to inspire opposition voters to the extent that the charismatic Corina Machado was projected to.

Years of perennial crisis and hardship have dramatically eroded President Nicolás Maduro’s (and the wider Chavista movement he represents) support. The regime has lost significant support in the traditional Chavista strongholds of poor urban neighbourhoods and rural states such as Barinas, Portuguesa and Sucre.

The governing United Socialist Party’s (PSUV) narrative has now pivoted away from lauding the achievements of the regime towards framing the opposition movement as a threatening force. González has been consistently portrayed as a “candidate of the empire” – an attempt to associate him as complicit in the US and wider West’s sanctions program that has crippled the Venezuelan economy.

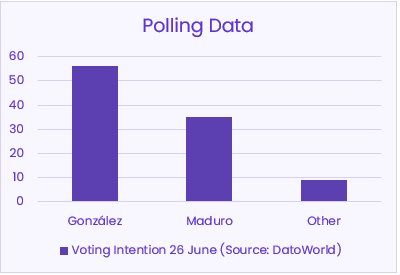

Accurate polling in Venezuela is difficult given the scale of state repression. However, the polling that has emerged has shown González with a substantial lead.

Another poll produced by the Venezuelan agency Megnálisis in early May gave González a lead of almost 50%, however the validity of this is uncertain.

Nonetheless, it is increasingly clear that González is the most popular candidate in the country. Corina Machado herself has claimed in an interview to the Financial Times that “we will win by a landslide. The only way that won’t happen is if there is monumental fraud”.

However, as the campaign unfolds, it is increasingly clear that the regime might be planning to do just that.

This is because as the campaign unfolds the regime has intensified its repression of the opposition. The NGO Provea alleges that at least 36 known opponents of the regime have been arrested since the start of 2024. Though the government has permitted opposition rallies, it has forcibly closed restaurants and hotels used by the opposition during the campaign. It is meant to discourage other businesses from assisting the opposition in any way.

Given the regime’s history of electoral suppression and the early signs exhibited during the campaign, the prospect of a totally free and fair election seems distant. This echoes the last poll held in 2018, which was immediately denounced by the international community and led to the imposition of devastating sanctions.

However, whether such measures will be imposed again is not totally clear. The raft of sanctions ultimately failed in their primary objective of dislodging Maduro. Instead, it inflicted widespread hardship on the Venezuelan people. This may make other regional nations reluctant to impose further sanctions that would deteriorate living conditions in Venezuela further, particularly as this would likely trigger another large-scale wave of emigration.

Nevertheless, the regime will be wary of appearing to outright rig the ballot. Instead, it is likely the government will utilise other, less overt means to influence the result.

The primary way the government will likely try to do this is to lower the number of voters who turn out on 28 July. This may come via changing the locations of polling sites at the last moment, or by imposing hurdles to vote in opposition strongholds. This can include deliberately understaffing selected polling stations to produce long queues to dissuade voters, or delaying the opening of polling stations on election day. This may be a fruitful tactics as historic PSUV heartlands in rural areas and on the outskirts of cities tend to be in comparatively sparsely populated areas, while opposition strongholds are often in dense areas prone to queues on election day.

Another tool for the regime relates to the weaponisation of the electoral register. The swift deadline imposed to register to vote meant many Venezuelans are now registered to different polling stations from where they reside. This may complicate voting for those who are internally displaced, which some estimates place at over one million people. It has been alleged the regime will facilitate its supporters to easily change their site of registration, but deny such privileges to opposition supporters. There are also over 7.5 million Venezuelans who have emigrated since the previous election, many of whom would likely vote against the regime. However, just 69,000 of these emigrants (1.7% of the potential voters) are now registered to vote in the election due to stringent criteria.

Although in a totally free and fair election Edmundo González would likely triumph, this prospect is increasingly unlikely. The Maduro regime is likely to utilise all available avenues to suppress and manipulate the democratic will of the Venezuelan people to cling onto power. In the process, violence on election day and the intensification of devastating economic sanctions are likely, deteriorating the quality of life further for many suffering Venezuelans.

Leave a comment below or ask us directly. For more information on our bespoke risk management services, book a call today. Order custom analyst papers like our Traveller Insight to stay informed and ahead of the curve.