With South Africa experiencing some of its worst blackouts in recent history, NGS risk analyst Gary Abbott, considers what the ongoing energy crisis means for the security environment and probes the likelihood of a repeat of July 2021, when widespread looting erupted in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng.

The ongoing energy crisis in South Africa raises valid concerns of a repeat of July 2021, when political grievances spiralled into generalised and opportunistic rioting and looting across KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and Gauteng, leading to considerable travel and operational disruption, with an estimated cost of USD3.3bn. Often overlooked, however, political mobilisation (be it opportunistic looting or general civil unrest) very rarely occurs in a wholly spontaneous and decentralised manner without some form of organisation. Looting and rioting can be seen to be the result of the combination of demand-side factors (the factors that drive the willingness for people to loot, such as economic deprivation) with supply-side factors (the factors that open the logistical and practical opportunities to loot).

Strikingly, not only has South Africa failed to address many of the demand-side factors that led to the July 2021 riots, but the ongoing energy crisis is exacerbating many of the underlying causes. In other words, the demand-side factors for looting are likely to be higher now than they were in 2021. In this sense, whether South Africa descends into a scenario similar to July 2021 is contingent on the supply-side, and whether the opportunities for looting present themselves. Despite the high economic costs of looting, there can be political incentives behind looting and anarchy, it can be a means to given political ends. With the ANC at one of the weakest points in its history, there are increased incentives for political agents to create conditions that are conducive to looting, which would further undermine the ANC’s ability to govern and thus increase electoral prospects or other political interests for respective political agents. Overall, South Africa is just as – if not more – vulnerable to looting now as it was in 2021.

Since 2008, Eskom – the state-owned utility provider that provides up to 90% of South Africa’s electricity needs – has implemented controlled blackouts (known locally as ‘load shedding’) to prevent the collapse of the electricity grid as demand outpaces supply. There are several important points on the energy crisis that warrant close consideration.

The former CEO of Eskom points to several causes of the electricity shortage: In an interview with eNCA aired on 21 February 2023, Andre Marinus de Ruyter outlines how South Africa went from a regional electricity exporter to having widespread outages in a mere couple of decades. First, Eskom has relied on coal to the detriment of investing and diversifying into other sources, leaving it extremely vulnerable to endogenous shocks (coal accounts for 80% of electricity generation). Relatedly, the coal fleet is almost 50 years old and has lacked modernisation, leaving it exposed to greater unreliability and unplanned maintenance measures. Third, political interests have overridden material ones, with members of the government pressuring the utility provider to defer short-term maintenance operations to ensure power at all times, in turn further degrading the state of the coal fleet. Finally, is the problem of corruption: in the eNCA interview, de Ruyter alleges that Eskom is penetrated by organised crime groups that commit acts of sabotage to then win lucrative repair contracts among other acts of corruption, alleging that such actors have links with high-ranking politicians. When he raised these problems to a senior government official, de Ruyter alleges he was told to “enable some people to eat a little bit”.

Rather than welcoming the concerns raised by de Ruyter (which predate the eNCA interview), members of the ANC and the government have attacked him. In November 2022, Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy, Gwede Mantasche, accused de Ruyter of behaving like a “policeman” and being too focused on “chasing criminals”. A month later, Mantasche accused Eskom of “actively agitating for the overthrow of the state” via conducting load shedding. Then, in February 2023, the ANC secretary-general Fikile Mbalula accused de Ruyter of being “right-wing”. A few days later on 26 February, the ANC threatened to file criminal charges against de Ruyter if he failed to present corruption evidence to law enforcement officers.

Eskom’s demise symbolises wider institutional and normative problems in the country: The ongoing energy crisis in South Africa is symbolic of wider institutional and normative problems, namely the problems of corruption, patronage, and the penetration of political structures by organised crime. The Zondo Commission investigating state capture (Part VI) recommended the criminal prosecution of all the living members of the Eskom board of directors that operated in 2014, besides Norman Baloyi who reportedly questioned certain contracts and was subsequently removed from his role. Relatedly, a report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime published in September 2022 (GI-TOC) claims that “organised crime is an existential threat to South Africa’s democratic institutions, economy and people”, while noting the “industrial scale” theft of copper, impacting an array of underlying infrastructure, including electricity. In contrast to the assaults lodged by the ANC and members of the government against de Ruyter that deny endemic corruption, the GI-TOC report highlights the “growing links between state and criminal actors…that can be termed ‘organised corruption’, blurring the line between upper and underworlds”.

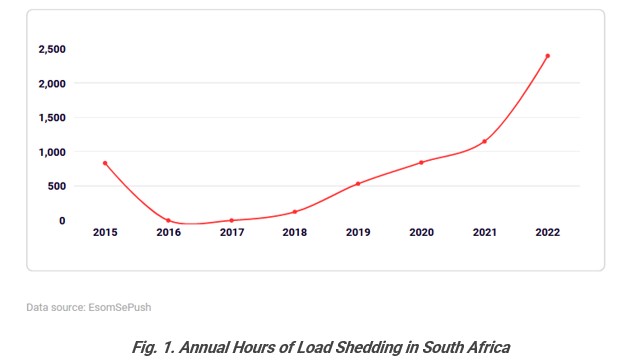

Load shedding is at its worst historically and has little scope for considerable improvement in the next couple of years: The intensity of load shedding has increased markedly in recent years (see Fig. 1). However, structural conditions mean that there is limited scope for considerable improvement over the next couple of years. Materially, the construction of new coal plants would likely take decades, while the construction of alternative energy sources, such as solar power farms, would likely take a couple of years. Although the privatisation and decentralisation of Eskom may slightly elevate the production of electricity by raising productivity and efficiency while reducing corruption, the ANC is likely to be ideologically opposed to such measures, while unions would likely mobilise and threaten even further energy shortages.

Additionally, the measures adopted by President Ramaphosa – such as the declaration of a state of emergency and the introduction of a new energy minister – are ad-hoc measures that will have a limited impact on the overall energy situation. In this regard, over the coming years, the stable provision of electricity is likely to be a decentralised responsibility for the private sector, specifically businesses and individuals, be it from solar or diesel generators.

Load shedding is increasing economic problems and grievances among the public: The ongoing energy crisis in South Africa is exacerbating interconnected extant economic problems in the country, such as widespread economic insecurity, high levels of youth unemployment, and trepidation felt by investors, which curbs capital flows into the country in tandem with offering headwinds to economic growth. While adding tailwinds to all such problems, the energy crisis signals to the needy their situation has little scope for improvement, elevating frustrations and the likelihood of a violent backlash, such as violent unrest and opportunistic looting.

Almost two years ago in July 2021, rioting and looting erupted across KZN and Gauteng, resulting in over 300 deaths, thousands of injuries, and estimated losses to the South African economy of USD3.2bn. The unrest was defined by blockades on major roads and large crowds looting an array of targets, including shopping centres, factories, warehouses, and residential properties, including the high-end City Life Pearl Towers building in Durban. Citing large crowd numbers and a reduced supply of tear gas and rubber baton rounds, state security officers were largely reduced to onlookers as anarchy engulfed parts of KZN and Gauteng, finding themselves unable to enforce an effective public order response.

To probe the likelihood of a return of widespread civil unrest and opportunistic looting as a result of the ongoing energy crisis, it is important to first reconsider several important considerations from the July 2021 riots.

The July 2021 riots were caused by multiple interlinked factors: The factfinding mission submitted to President Ramaphosa highlighted that the riots of 2021 did not have a single cause, but resulted from several interconnected factors. These included high levels of unemployment – youth unemployment in particular – with no apparent plan to fix it; the failure of weak state institutions to offer the provision of basic social services; widespread corruption at every level of government; the problems of state capture, where public services are hijacked by corrupt and private interests; and the problems of overcrowding and poor living conditions in townships and informal settlements. In other words, numerous demand-side factors increased the incentives for people to engage in looting, primarily concerning economic and human deprivation.

Although the fact-finding report did note elements of political interference, the majority of looting and rioting that occurred was opportunistic and spontaneous. Initially, political grievances over the incarceration of former-President Zuma sparked organised unrest, in the form of trucks and cars being set on fire on the National Route 3 at Mooi River Plaza. However, the report highlights the problem of “organised spontaneity”, where individuals with alleged allegiances to Zuma called on social media for people to mobilise, while others went from shopping centre to shopping centre sparking looting. The report notes that political actors were hoping to trigger looting to render the country ungovernable and thus prevent the trial of former-President Zuma. In one instance, minibuses were known to have travelled from KZN to Gauteng before travelling to several shopping centres and started looting. Then, individuals from both formal and informal settlements – including the elderly and children – opportunistically looted when they realised the limited police reaction. The report highlights how some non-governmental organisations viewed the events as “bread riots”, with many of the looters being deprived people looting essential items. The majority of shopping centres and warehouses looted were located near informal settlements, where residents – witnessing unrest with no apparent police reaction– flooded the nearby streets and joined in on the unrest.

In this regard, looting is a two-step process that is the result of the culmination of both demand and supply-side factors; looting is unlikely to occur purely as a result of economic deprivation. For looting to occur, it requires political agents to create an environment that is conducive to looting, which can be a means to their respective political ends. In the case of 2021, it was “organised spontaneity”, where political actors – with alleged support for Zuma – triggered looting themselves, which in turn attracted onlookers and bystanders.

The police were unable to enforce the rule of law and protect private property: The initial days of unrest were defined by widespread looting that appeared to occur with impunity. Citing logistical problems surrounding the widespread nature of unrest coupled with shortages of vital equipment, police officers were often mere onlookers to the anarchy taking place, leading to a growth in vigilantism. Protecting private property became a responsibility of local individuals, often business owners and local citizens defending their communities and vital infrastructure.

The unrest was only curbed with the deployment of the military: The failures of the police to stop the unrest prompted the initial deployment of 2,500 soldiers, which eventually shifted to the deployment of approximately 25,000 military personnel. The increased operational footprint by the security forces was successful in stopping the widespread looting, largely on the back of the increased costs associated with unrest; the greater security presence increased the likelihood of punishment, decreasing the incentives to conduct looting. Nevertheless, the nature of the deployments meant that they were largely reactive, looting would occur and it would take time for effective public order measures to be implemented.

The state failed to punish those responsible: Although 5,550 people were arrested in connection with the unrest, by August 2022 only 50 individuals were convicted according to Defence Minister Modise. This raises fears of setting a worrying precedent, namely that widespread looting will not necessarily result in government sanction, increasing the likelihood of repeat events.

From this brief assessment of the context behind the energy crisis and a reconsideration of July 2021, one can finally probe what the ongoing energy crisis means for South Africa and its security environment. With minimal scope for considerable improvement over the coming couple of years, the next section points to a security environment that shares stark parallels with the undercurrents that sparked the widespread looting of July 2021, suggesting that South Africa is prone to widespread political unrest and opportunistic looting. The key question, however, is whether political agents will again find incentives to create an environment conducive to looting.

The incentives for looting are likely to increase over the coming two years: Strikingly, many of the demand-side factors that contributed to looting in July 2021 (such as limited job opportunities, high levels of inequality, corruption, the failures of state institutions to offer basic social services, widespread corruption, and overcrowding in townships) have failed to be addressed. In fact, with blackouts costing the economy USD24bn in 2022 alone according to the World Bank, the energy crisis exacerbates many economically derived demand factors while curbing growth potential by deterring investment and limiting capital flows into the country, reducing the scope for improvement. Added to these concerns are the increased operational costs and bottle-necked supply chains, which risk inducing endogenous inflation by passing on increased operational costs to consumers. Overall, the demand-side factors for looting are likely higher now than in 2021 and are only likely to worsen over the coming years due to the energy crisis.

Looting is unlikely to be entirely spontaneous: As with most forms of political mobilisation, it is unlikely that opportunistic looting will occur wholly spontaneously in a decentralised manner without some form of organisation. The previous section noted that the looting in KZN and Gauteng was primarily triggered by political agents that took advantage of human deprivation as a means to their respective political ends, posting on social media and calling for mobilisation while sending vehicles to several shopping centres to spread the unrest. In other words, the demands for looting are felt nationwide so its manifestation rests on the moves of political actors to create environments conducive to anarchy or looting.

The energy crisis undermines the legitimacy of the ANC and increases the incentive structures for political agents to trigger looting: As seen in November 2021, when the ANC’s support fell below 50% in local elections for the first time, the ANC is at one of the weakest points in its history. With the general elections scheduled for 2024 set to be some of the most competitive in the country’s recent history, there are increased incentives for political agents to again take advantage of widespread human deprivation and utilise “organised spontaneity” to further undermine the ANC’s perceived ability to govern. As seen in July 2021, anarchy and looting can be a means to certain political ends (in the case of 2021, the interruption of the Zuma trial). Contemporarily, the weakness of the ANC is likely to increase the incentives of triggering unrest and looting to further undermine the ANC’s apparent ability to govern, perhaps in a bid to increase electoral prospects or other political interests (such as factionalism within the ANC itself).

Locations in close proximity to areas with high levels of deprivation are most at risk of looting: As seen in the previous section, the majority of looting that occurred in July 2021 was by the needy, who often flooded onto major streets from their nearby townships. Although the unrest occurred primarily in KZN and Gauteng provinces, this was a result of political agents who supplied the opportunity for looting (by instigating it); the demand-side factors that influence the willingness to loot are and were felt nationwide. In other words, although the looting of July 2021 was largely restricted to KZN and Gauteng, this was a result of where looting opportunities were supplied; the entire country is ultimately exposed to the vulnerability of looting. Nevertheless, the majority of individuals that engage in looting are likely to be the needy, so although looting could erupt nationwide, it is most likely to occur in close proximity to areas with high levels of deprivation.

The protection of property is likely to be the prerogative of private citizens: In the event that widespread looting again returns to South Africa, it is likely to follow previous trends: the protection of private property is likely to be the prerogative of citizens and security contractors. The riots of July 2021 revealed the state’s inability to implement effective public order measures in the face of widespread unrest. Although equilibrium eventually returned to the streets with the deployment of the army, it took time before soldiers regained control of the situation. In other words, although this means that future unrest is likely to be met by quicker deployments of the army, their deployments will be ad-hoc and are most likely to protect vital infrastructure such as food and energy installations, or governmental buildings. This means that the protection of residential or commercial property is likely to be the prerogative of private security contractors, until the army can regain control (which is also contingent on the scale of the looting).

Civil unrest is likely to increase in scale and frequency: The hardship inflicted by blackouts is felt by an array of actors, largely irrespective of financial background and geography. This increases the demand and appeal for change, which in turn increases the mobilisation potential for social movement organisations (SMOs; such as trade unions or other pressure groups). In this regard, the grievances felt by South Africans are likely to result in greater political mobilisation and activity by SMOs, as already seen with the national shutdown organised by the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) on 20 March 2023. Going forward, not only is the country vulnerable to looting and its affiliated disruptions, but protests are likely to increase in both their scale and frequency, offering further travel and operational concerns.

Although concerns abound about a repeat of July 2021, it is important to appreciate that looting is the culmination of political factors, namely the willingness to loot (the demands) coupled with the practical and logistical opportunities to do so (the supply). On the former, the energy crisis exacerbates human deprivation while being symbolic of wider institutional and normative problems in the country, namely corruption and mismanagement. In this regard, with the demands for looting among the population likely to be higher now than they were in 2021, whether anarchy and looting again return to South Africa is largely a question of supply and whether the political incentives arise again to do so. Concerningly, with the elections scheduled for 2024 set to be some of the most competitive in the country’s history, there are no shortages of political appeals to further undermine the ANC’s ability to govern, whether this be from members of the opposition or even disenfranchised factions within the ANC itself, as with July 2021. In this regard, South Africa is as vulnerable to anarchy and looting now as it was in July 2021 if not more. Whether political actors choose to do so, however, remains to be seen.

Author: Gary Abbott, Risk Analyst, Northcott Global Solutions

Contact: risk@northcottglobalsolutions.com

Northcott Global Solutions provides risk assessments, tracking, security escorts, personal protective equipment, remote medical assistance and emergency evacuation.

DISCLAIMER:

Material supplied by NGS is provided without guarantees, conditions or warranties regarding its accuracy, and may be out of date at any time. Whilst the content NGS produces is published in good faith, it is under no obligation to update information relating to security reports or advice, and there is no representation as to the accuracy, currency, reliability or completeness. NGS cannot make any accurate warnings or guarantees regarding any likely future conditions or incidents. NGS disclaim, to the fullest extent permitted by law, all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on content and services by any user with respect to acts or omissions made by clients on the basis of information contained within. NGS take no responsibility for any loss or damage incurred by users in connection with our material, including loss of income, revenue, business, profits, contracts, savings, data, goodwill, time, or any other loss or damage of any kind.