Following a year of unprecedented geopolitical developments, forecasting the shape of the world in 2023 is possibly harder than ever. Nonetheless, here NGS Risk Analyst Jason Davies considers the impact of political and security developments throughout 2023 on international relations, and how they will have an impact on international travellers.

This year has seen political and economic developments that have surpassed most reasonable expectations. On 24 February, the status quo of relative stability in Europe was completely shattered when Russian forces initiated a ‘special military operation’ against Ukraine; plunging the continent into the most serious conflict since the Second World War. Because of this altercation, the year ahead will likely experience fluctuations in global supply chains, most notably in energy, food, and raw materials.

More acutely, the short and long-term stability of some nations will be determined by the conduct and the aftermath of several elections that threaten to exacerbate already significant tensions. Civil unrest and political violence, already common in Brazil and Pakistan, may reach new proportions in the new year. Furthermore, the urge to democratise may drive instability in countries where upcoming elections are likely to be manipulated in favour of the ruling party.

The further normalisation of COVID-19 – the consequence of slumping economic progress in medium and high-income economies and growing discontent with health mandates – is certainly going to be a theme that continues into 2023, providing incidence rates remain stable. Even so, the civil unrest seen in China at the end of 2022 demonstrates that there are limits to the forms of control exercised in the name of public health.

Key Event: Russo-Ukrainian War

Key Risks: Operational Disruption, International Conflict, Economic Instability

The year ahead in Europe is likely to be dominated by the war in Ukraine and its associated disruptions, as well as any secondary effects that the conflict will bestow on the rest of the continent. Economic woes stemming from the conflict and the aftermath of COVID-19, as seen by increasing inflation and stagnating growth, are forecasted to continue into the start of the new year. On a national level, elections in Poland, Spain, the Czech Republic, and Finland threaten to promote more divisive politics, with civil unrest being a likely medium of discontent.

The climax of Ukraine’s southern counteroffensive was the liberation of the city of Kherson; the only regional capital that the Russian military was able to capture since the start of its invasion. This is a notable milestone for Ukraine but does not mark a definitive turning point in a war that Vladimir Putin must present as a victory to his people. While this remains a factor, the continuation of the conflict and its associated disruptions looks likely for the duration of 2023.

The casus belli and the subsequent conduct of the combatants have ensured that the war is very much a global affair with vested interests from a multitude of state and non-state actors. Because of these factors, non-belligerents have been victims of accidents, political grandstanding, and subterfuge. The gradual closure of Russian-owned pipelines from June has demonstrated Europe’s vulnerability to foreign gas supplies. Furthermore, the 15 November power outages and the deaths of two individuals in Polish territory – both coinciding with Russian missile strikes – have shown how intertwined this conflict is with continental stability.

While relations between Moscow and Kyiv have naturally been adversarial, the two have brokered agreements that consider some of these wider implications, especially in developing countries. In November, the Black Sea Grain Initiative was renewed for four months which will decrease the likelihood of global supply chain issues. The deal, brokered by Ankara and the United Nations, has been responsible for the safe transportation of 12.7 million tonnes of Russian and Ukrainian cargo, helping stabilise food markets worldwide. Before the renewal, Moscow had temporarily halted its participation in the deal, the consequence of an attack on its naval base of Sevastopol in late October. An attack of a similar nature may derail the prospect of future negotiation, leading to operational disruption and instability in vulnerable markets.

Economic deprivation has traditionally been linked with an increase in populism and radical forms of politics. As the Ukraine war and the effects of COVID-19 threaten to stagnate European economies in 2023, far-right and separatist parties may gain traction in European elections; Poland and Spain being notable examples. Aided by the socioeconomic tensions already existing in these countries, civil unrest is a possible outcome during and after these elections.

Key Event: Pakistan General Election

Key Risks: Civil Unrest, Crime, Political Violence, Travel Disruption

In the latter half of the new year, two major general elections in Pakistan and Bangladesh will likely exacerbate already dangerous levels of political violence. Disruptions in Thailand and Cambodia during their electoral periods may occur as a response to increasing oppression and dissatisfaction about transparency. In the background, Beijing will likely continue to posture over Taiwan while establishing a future that accommodates COVID-19.

In November 2022, former prime minister and current leader of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) Imran Khan was shot during an anti-government rally in Wazirabad, the climax of increasing violent sectarian tensions. Throughout the year, there has been a multitude of clashes between the country’s security forces and the supporters of Khan, who believe that he has been unjustly persecuted by establishment individuals. This impression was not helped by an October decision by the electoral commission which barred Khan from holding public office, potentially hindering his prospects in 2023. If this judgement is sustained for the election (which must be held by October at the latest), civil unrest, travel disruption, and political violence will most likely occur across the country; the same if Khan is allowed to participate but loses.

Similar scenes may unfold in Bangladesh’s general election which is set to occur around the end of the year and will likely involve voter intimidation and violence if historical trends are to continue. In December 2022, protests organised by the Bangladesh National Party (BNP) involving tens of thousands of individuals preceded the arrest of opposition leaders and violent clashes which have killed at least one person. The purpose of the demonstration was to compel the resignation of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and the dissolution of parliament to trigger new elections, an unlikely event as the ruling party would consider it imprudent. As the deadline for an election draws near, the government will probably attempt to further delegitimise the opposition and their base, a move which could encourage further unrest and violence.

Government repression, human rights abuses, and distrust in their electoral systems have been received poorly in both Thailand and Cambodia over recent years; prompting sporadic bouts of civil unrest which have been violently suppressed. The resentment from these factors could incite further conflict during Thailand’s general election on 7 May and Cambodia’s parliamentary election on 23 July. In the South China Sea, Beijing will continue to antagonise the United States over the issue of Taiwan, but realistically, nothing of substance is likely to happen. More importantly for China, as seen with its people’s grievances over draconian health mandates, the regime will strategise towards a post-COVID future that will allow for continued economic growth.

Key Event: Civil Unrest in Iran

Key Risks: Civil Unrest, Crime, Political Violence, Travel Disruption, Operational Disruption

Civil unrest in Iran, which is likely to continue because of punitive government responses, will immediately characterise the start of 2023 in the Middle East. The Turkish general election in June threatens to expose the weakness of Erdoğan’s premiership, especially if sectarian conflict is allowed to become more pronounced. Less notable, but still significant, is the 75th anniversary of the Palestine Catastrophe.

The death of Mahsa Amini in police custody in September 2022 preceded huge amounts of civil unrest and violence not seen since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The broad social movement, which is largely advocating for regime change and the abolition of stringent religious laws, has experienced hundreds of fatalities at the hands of security forces that can operate with near impunity. Although it does not yet constitute a mortal threat to the current regime, the unrest has brought widespread disruption to the country with strikes, road blockades, and internet blackouts being regular occurrences. This unrest will likely continue into the new year, with state excesses – such as public executions – breathing new life into the demonstrations. A sudden and ubiquitous escalation could theoretically lead to nationwide martial law and the unrestricted use of government force against perceived dissidents.

In December 2022, opinion polling did not give Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan the 50% of support required for an instantaneous win in the general election set for 18 June 2023. This does not necessitate loss for Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP), especially when one considers their influence on the branches of the state. To increase his legitimacy, Erdoğan will need to galvanise his nationalist base which may be seen in the further suppression of the Kurdish people and any parties affiliated with them, such as the Peoples’ Democratic Party. The Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which has conducted an insurgency in the south-east of the country, may conduct attacks or promote civil unrest in Turkish urban centres if Erdoğan pursues this course of action. Ethnic divisions aside, democratic backsliding in Turkey has been an issue of consternation among liberal voters, who are likely to protest during the electoral timeline.

15 May marks the 75th year of Nakba (the Palestinian Catastrophe), a day that commemorates the destruction of the Palestinian homeland and the persecution of its people after the establishment of the State of Israel. In 2011, Palestinian refugees and other individuals approached Israeli military checkpoints, prompting altercations which resulted in over one hundred casualties, including fifteen dead. Other years have seen similar incidents, and the coming anniversary may see demonstrations, the deliberate provocation of security forces, and the potential use of violent force against protesters near Israel’s borders.

Key Event: Prospective Sudanese Election

Key Risks: Civil Unrest, Crime, Political Violence, Travel Disruption

Elections all over Africa throughout 2023 will bring economic and political issues to the foreground, especially in countries that have experienced authoritative rule in recent years. This will be most acute in Sudan, where elections have been promised amidst growing civil unrest by anti-coup demonstrators. Other contentious elections will occur in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In Ethiopia, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed will need to prevent sectarian tensions from reigniting civil war in the region of Tigray.

In October 2021, Sudanese army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan seized power in a coup, plunging the country into further political and economic turmoil. Since the coup and the entrenchment of the military as the primary authority in the country, civil unrest and political violence have been continual, claiming hundreds of lives. The government has repeatedly stated that the status quo is temporary, with national elections scheduled for July 2023 to reinstate civilian government. Any election that is not perceived as free and fair, or is postponed, will certainly promote further unrest and violence. Although Burhan has pledged that his government will exit politics after this election, there is a possibility that the military will have a crackdown to control the outcome of the election and gain a semblance of legitimacy.

Government incompetence and corruption, increasingly desperate economies, and poor responses to COVID-19 are likely to be catalysts for further unrest in several African countries, especially as elections draw near in Nigeria (25 February), Sierra Leone (24 June), Liberia (expected 10 October), and the Democratic Republic of Congo (20 December). These countries have already experienced varying levels of civil unrest because of the aforementioned issues, with further disruptions a likely possibility in the new year. The British government has also expressed concern that Nigeria’s electoral period might be impacted by terrorist activity, particularly from militant groups.

After two years of civil war in the region of Tigray, a peace agreement was made between the federal government of Ethiopia and the principal combatants in November 2022. Despite immediate grievances – such as terrorist designations – being resolved in the negotiations, underlying tensions and ethnic divisions may be a barrier to a sustainable peace. In 2023, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed will need to ensure that the Tigrayan people feel included in what is a very diverse federal state; an issue that has instigated a several-decade insurgency in the region of Oromia. The absence of a constructive dialogue could renew hostilities in the Tigray, which has the potential to spill over into other regions.

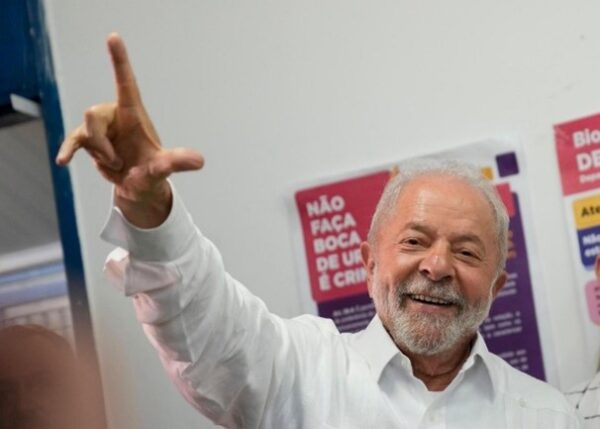

The new year in the Americas will be immediately marked by President Lula’s inauguration in Brasília, a contentious affair which is likely to be accompanied by political violence, travel disruption, civil unrest, and crime. Elsewhere, elections in Paraguay, Guatemala, Argentina, and Cuba may instigate waves of civil unrest, especially as economic concerns move to the foreground of their respective political debates.

The Brazilian general election in October was defined by its violence between the supporters of Jair Bolsonaro and Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva with acts of murder, abduction, and sexual assault commonly reported. The announcement of Lula winning the election with a slim margin of 1.6% preceded mass civil unrest and an attempt by the Bolsonaro camp to formally disqualify the results. Tensions have not diminished in the succeeding weeks and on 13 December, supporters of Bolsonaro set vehicles on fire and attempted to storm the federal police headquarters in Brasília.

With a politically charged atmosphere that is continually displaying itself in acts of violence, Lula’s inauguration on 01 January will likely be met with at least civil unrest. Less likely, although plausible, could be an event similar in character to the 06 January Capitol attack in the United States. This is not impossible considering Bolsonaro’s reluctance to concede defeat in conjunction with the violent acts already orchestrated by his supporters. The Three Powers Plaza will be the epicentre of any eventuality considering its proximity to the inauguration; with travel disruption and civil unrest being expected here, and political violence being possible.

In 2021, protesters mobilised all over Cuba against the ruling Communist Party and its mismanagement of the economy. During this unrest, the security forces responded with a brutal crackdown involving hundreds of arrests and numerous human rights abuses. There is a possibility that disruptions will renew during the timeline of the 2023 parliamentary elections; the first in which the Castro brothers are not principally involved. The Paraguayan general election on 30 April and a possible Peruvian election in December may also be tumultuous affairs, where government dissatisfaction could manifest itself into civil unrest.

Northcott Global Solutions provides risk assessments, tracking, security escorts, personal protective equipment, remote medical assistance and emergency evacuation.

Author: Jason Davies, Risk Analyst, Northcott Global Solutions

DISCLAIMER:

Material supplied by NGS is provided without guarantees, conditions or warranties regarding its accuracy, and may be out of date at any time. Whilst the content NGS produces is published in good faith, it is under no obligation to update information relating to security reports or advice, and there is no representation as to the accuracy, currency, reliability or completeness. NGS cannot make any accurate warnings or guarantees regarding any likely future conditions or incidents. NGS disclaim, to the fullest extent permitted by law, all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on content and services by any user with respect to acts or omissions made by clients on the basis of information contained within. NGS take no responsibility for any loss or damage incurred by users in connection with our material, including loss of income, revenue, business, profits, contracts, savings, data, goodwill, time, or any other loss or damage of any kind.