Former police officer Derek Chauvin is currently standing trial in the United States on charges of manslaughter and second- and third-degree murder following the death of George Floyd last summer. The death of Floyd, an African American, while in the custody of Chauvin, a white police officer, sparked outrage and reignited racial tensions in the US. Civil unrest followed in states across the country as thousands of protesters called for justice for Floyd, for the police service to be defunded and an end to racism. Unrest subsequently reverberated around the world, inspiring many similar movements abroad and causing concern about travel disruption and localised violence.

Last year’s unrest saw large-scale and long-lasting protests that on numerous occasions escalated into looting and rioting that caused damage to private property. This year, with the trial so high-profile, tensions have once again erupted into unrest. The recent return of protests to Minnesota in mid-April, the epicentre of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protest movement last summer and the location of the trial, has demonstrated the volatility of relations between the African American community and the police force. However, since the first outbreak of unrest last year a number of contextual factors have changed, both domestically and internationally, which risk creating greater operational disruption and violence.

Civil unrest this year began after a similar incident of police violence, namely the death of another African American man, who was shot by police following a traffic stop. Other dates of significance that may heighten unrest include the day of the verdict (expected late April / early May) and the first anniversary of Floyd’s death (25 May). While unrest has broken out near the location of the recent police violence, it is likely to spread to other areas which saw BLM protests last year, including urban centres, central boulevards, police stations and government buildings.

In the time since last year’s protests, other issues of racial significance have occurred in the US, which make these locations more likely to experience unrest. Recent high-profile incidents include the controversial changes to Georgia’s voting laws and the pepper-spraying and arrest of an African American US Army lieutenant in Virginia. However, not one US state is exempt from the possibility of an incendiary incident between the African American community and the police force, meaning that unrest could begin anywhere across the country.

Last year, many private businesses were targeted in looting that seemingly had no relation to the protest movement other than being located along protest routes or within areas of rioting. Frustrations seemed to drive the protests and rioting, rather than a strategic objective or obvious leadership to which actions were accountable. A similar scale of escalation to last year’s protests risks travel disruption, with some city areas becoming ‘no-go’ zones due to the presence of protesters or the risk of confrontations between groups and security forces. The construction of self-declared “autonomous zones” in Portland and Seattle last year caused localised business and travel disruption for long periods before the camps were eventually dismantled by the security forces.

This year, concerns are heightened about the potential reaction of far-right groups to unrest following a year of divisive politics. Last year there were numerous confrontations between groups, which included targeted attacks in which vehicles were driven into crowds of BLM protesters. A further concern is an increase in hate crime against non-white groups. In the US, there has been a recent rise in anti-Asian hate crime, which has expressed itself in assaults and small arms attacks against people of Asian descent. BLM protests could worsen relations between races within America, and encourage a further increase in hate crime against non-whites.

Figure 1: A police car on fire during a protest march against police violence. Los Angeles. 30 May 2020. (Shutterstock)

Figure 2: A looted store in the aftermath of riots in Minneapolis. 28 May 2020. (Shutterstock)

The most obvious factor that will affect the severity of civil unrest is the trial’s verdict. If Chauvin is handed a not-guilty verdict or acquitted, unrest is likely to be violent and widespread. While a guilty verdict may be expected to placate BLM protesters and reduce the probability of large-scale violent unrest, there remains the likelihood that supporters will use the moment in the media’s spotlight to highlight other related causes, or that opposing groups, such as the Proud Boys, will protest against the verdict.

As seen last year, the reactions of US police forces varied between states; while some police forces stood back and knelt with BLM protesters in attempts to demonstrate solidarity and help de-escalation, others encouraged the deployment of the National Guard. An overly aggressive police response emboldened by resentment towards protesters is likely to worsen violence. Footage of an officer pushing over an elderly man during the height of protests in 2020 only strengthened public opinion against the police. Any similar incidents, especially where the victim is non-white, will reinforce and serve to validate the cause of BLM protesters, prolonging unrest. On the other hand, targeted violence against police officers by BLM supporters may encourage the participation of far-right groups, and increase the risk of other officers reacting excessively to threats, risking further casualties.

Contrasting police approaches to the January 2021 riot at the Capitol Building and the BLM protests in 2020 highlighted the differences in the police’s risk perception, which was assumed to be based on ethnicity. If the same security response is applied to future race-related protests, the police risks worsening relations with minority communities, while missing opportunities to mitigate escalation by far-right groups.

Civil unrest has once again broken out in Minneapolis after an African American man was shot and killed by police officers following a traffic stop. The incendiary nature of this incident demonstrates the extremely volatile relationship between the US police force and the African American community. While tensions are high in Minneapolis, the epicentre of unrest last summer and now home to Chauvin’s trial, other parts of the US are as likely to experience such incendiary incidents over the course of the trial, risking future unrest.

Additionally, the prevalence of mobile recording devices at the scene of an incident and their viral nature mean that unrest can quickly spread to areas with no relation to the incident. In the case of Floyd’s death, recordings of the incident spread around the world over social media and provoked international solidarity protests. Furthermore, the use of recording devices by members of the public can, in routine police situations, make officers react defensively possibly worsening a situation: an officer is less likely to acknowledge a mistake in their work on camera when potentially millions of people could be watching them across social media.

Bipartisan divisions stoked unrest during 2020 with BLM protests treated as a leftist political movement by many of those on the political right. Democrat politicians were accused of ignoring the unrest in order to destabilise the re-election bid of President Trump. Far-right groups that publicly supported Trump were active in their opposition to the BLM protests, and, in some cases, this led to violent confrontations. However, with a Democrat in the White House and Trump’s divisive rhetoric without the platform of the campaign trial, potential protests are less likely to be seen as a partisan movement, dissuading some from joining protests and potentially reducing their scale.

Nonetheless, in the time that has elapsed since last summer’s protests, the position of right-wing America has changed with Trump’s election defeat and his subsequent promotion of a rigged election conspiracy theory. Far-right groups emboldened by his rhetoric, as seen in Washington D.C. in January 2021, are likely to re-enter into clashes with BLM protesters, causing violence and serious injury, possibly to a greater extent than last year.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has provided the context to both last summer’s unrest and this year’s trial, circumstances have changed since Floyd’s death. Now, death rates in the US are falling while vaccination rates are increasing. By 12 April, 35% of the population had received at least a first vaccine dose. The Biden administration has sought to actively engage in virus suppression strategies, a stark difference from President Trump’s refusal to acknowledge the severity of the virus, which was killing African Americans at a rate twice as fast as white Americans. With the US now appearing to be over the worst, the sense of disenfranchisement towards the federal government that surrounded the Trump administration’s lacklustre pandemic response may now be dissipating. With the US set to return to economic growth this year and vaccinations widely available, these steps towards normality may reduce the propensity for unrest to escalate this time round.

However, a year on from the beginning of the pandemic that has slowed global trade and increased unemployment, many Americans will now be financially worse off. Exacerbated by the global economic slowdown, poverty rates in the US are estimated to have increased by 2.4%, while the rate for African Americans increased by 5.4%. This disproportionate effect on African Americans increases the risk of unrest, as members of this community are likely to have grown frustrated over the unequal deterioration of their economic circumstances and declining living conditions, and may choose to protest their dissatisfaction.

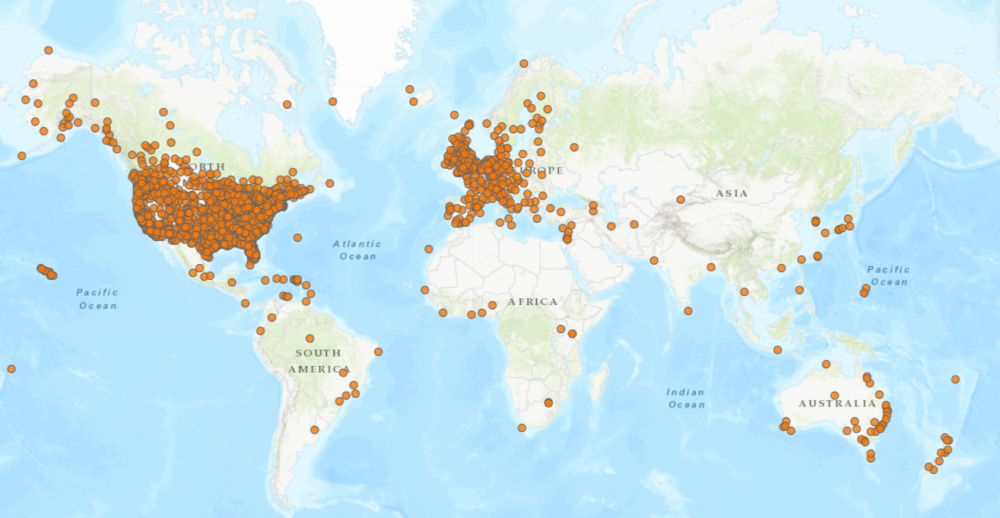

Protests last summer spread quickly across the globe and shone a light on issues of racism and police brutality in countries beyond the United States. Thanks to the interconnectivity of people around the world, the viral nature of online videos and the promotion of the BLM movement in pop culture and sport, many similar protests movements sprung up globally. If unrest in the US develops to the scale seen last year, there is a possibility that violence and unrest will spread again across borders to other countries.

With a third wave of COVID-19 circulating in many countries, a year of setbacks and lockdowns may provide ample incentive for people to protest against the police, who have largely been responsible for enforcing restrictions. This was true last summer in South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya where protesters decried the police for deaths related to the enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions. Police violence remains a lingering issue in African countries, and an untimely incident of police violence on the continent could provoke unrest that capitalises on tensions in the US.

In Brazil, where BLM protests erupted in 2020, the misguided leadership of President Bolsonaro through the pandemic has been blamed for the increasingly dire death rate from COVID-19. The risk of BLM protests returning is increased by the likelihood that they would be combined with anti-government protests. In the wider region, Mexico’s active feminist movement may combine itself with the momentum of the BLM movement. The death of a female migrant in police custody in March 2021 caused protests in various urban centres, demonstrating the overlap between race and gender discrimination in Mexico, and the potential for reactionary unrest.

In Europe, a re-emergence of BLM protests could provoke a large backlash. Since BLM protests last summer in the United Kingdom, there has been growing ‘anti-woke’ sentiment (the ‘woke’ agenda has being widely associated with the BLM movement). Repeat protests in the UK may see a greater anti-BLM reaction in the form of counter-protests and clashes. In other European countries, particularly France, a return of BLM protests may inadvertently lead to an increase in anti-migrant sentiment by those who object to the BLM movement seeking cultural change. Resentment towards the imposition of foreign values on the country creates a risk of reactionary violence being directed towards those who are foreign nationals, or who do not typically look like the locals. In other Western democracies, such as Australia and Canada, solidarity protests are likely, but would be expected to target domestic issues such as discrimination towards native populations.

Figure 3: World map showing locations that held BLM protests between 25 May 2020 and 18 November 2020 (Alex Smith/Creosto Map).

While the trial has brought a temporary media spotlight to the issue of racial discrimination in the US, the problem is a long-standing one and is likely to continue causing unrest for a while yet. However, while the trial is ongoing and the verdict awaited unrest has the potential to spread and worsen in severity. Tensions are currently extremely volatile within the African American community as demonstrated by the recent outbreak of unrest in Minnesota.

In the year since Floyd’s death a number of factors that may affect the spread and severity of unrest have changed, such as the government and the state of the COVID-19 pandemic. The extent to which these factors alter the propensity for large-scale civil unrest is determined by domestic and international contexts that will influence the escalation of protests and reactions, and consequentially the risk of business and travel disruption.

Accordingly, companies sending travellers abroad during this period of potential unrest will need to consider the risk profile of their staff, ensure they are appropriately prepared to react and have the necessary emergency evacuation plan in place in the event of a potential incident.

DISCLAIMER:

Material supplied by NGS is provided without guarantees, conditions or warranties regarding its accuracy, and may be out of date at any time. Whilst the content NGS produces is published in good faith, it is under no obligation to update information relating to security reports or advice, and there is no representation as to the accuracy, currency, reliability or completeness. NGS cannot make any accurate warnings or guarantees regarding any likely future conditions or incidents. NGS disclaim, to the fullest extent permitted by law, all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on content and services by any user with respect to acts or omissions made by clients on the basis of information contained within. NGS take no responsibility for any loss or damage incurred by users in connection with our material, including loss of income, revenue, business, profits, contracts, savings, data, goodwill, time, or any other loss or damage of any kind.